These days, if you sit down to watch the news, you’re almost guaranteed to hear someone talk about ‘the market’. ‘The markets are down today’, they’ll say, or ‘the market won’t like that’. More and more frequently it’s that ‘the markets demand action’, as the threat of recession looms.

These days, if you sit down to watch the news, you’re almost guaranteed to hear someone talk about ‘the market’. ‘The markets are down today’, they’ll say, or ‘the market won’t like that’. More and more frequently it’s that ‘the markets demand action’, as the threat of recession looms.

In this context, it is somewhat surprising that no-one asks: what exactly is ‘the market’, and why are we so beholden to it’s mood-swings?

In the classical days of political economy, Adam Smith and David Ricardo conceived of ‘the market’ as a government-regulated mechanism for the promotion of human well-being. As men who’d grown up under the shadow of 17th Century bread-riots, both saw price-fixing as futile and at times even counter-productive. They argued that if government could guarantee certain basics – property rights and contractual exchange – then the ‘invisible hand’ of profit-driven human interaction would lead to a balance of supply and demand and a more stable distribution of bread for all.

In his discussion of ‘Capital’, Marx built on this analysis. He argued that the division of production into investors, land-holders and workers, and the state guarantee of competitive exchange between them, underpinned a period of innovation and growth the likes of which human beings had never before seen and from which many derived great benefit.

Neither Marx nor the political economists saw ‘markets’ as perfect, however. Adam Smith, wrongly cited as the father of free-market economics, constantly cautioned against the unregulated power of big business, warning that unchecked ‘trade or manufacture’ would engage in ‘conspiracy against the public or in some other contrivance to raise prices’, since business interest ‘is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public’. Marx and his followers went further, arguing that some of what we value cannot be translated into monetary gain and thus will not be provided in a world run solely on the basis of profit (health-care for the poor being a good example).

Over the next century, economists developed mathematical models to explain how else markets ‘fail’. One example concerns the problem of ‘externalities’. These are side-effects that arise from the process of production. Ordinarily, the price of what I sell reflects what it cost me to produce. In some cases, production generates side-effects that are costly for others but not for me. In this scenario, unless I am forced by government or those who pay for these side-effects to change my mode of production, the drive for profit means that I’ll continue producing, irrespective of how bad this is for others. This is what happens with pollution, described by the government’s ‘Review on the Economics of Climate Change’ as ‘the most spectacular example of market failure we have ever seen’.

It is of course against this backdrop that government regulation and welfare-state capitalism developed and flourished. Aware that ‘the market’ is really just a term we use to describe the imperfect set of rules, regulations and institutions that sometimes fail but which often facilitate economic exchange in the service of human well-being, post-war governments tightly regulated business practices and used high income-taxes to fund the service provision that the profit-motive alone would never guarantee. It is no coincidence that this period saw the fastest and most equally-distributed rise in living standards in European history.

But that all changed in the 1970s. In the context of crisis, a new group of politicians and business leaders began promoting the idea that an economy could only function ‘efficiently’ in the absence of any government ‘interference’. In their narrative, profit alone guarantees economic and social well-being, while regulation stifles economic activity. Their diagnosis has been the removal of legislative barriers to the free flow of business – including taxes, environmental protection and labour laws – and the privatisation of publicly-provided services.

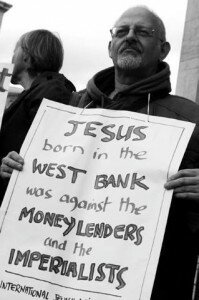

It is against this backdrop that ‘the market’ has been loosened from its metaphorical moorings. As the statements at the start of this piece indicate, we no longer see ‘the market’ as short-hand for one of the many mechanisms through which government provides for society. Today, ‘the market’ is conceived as a thing in itself, a living entity that ‘threatens’ us and our leaders and which determines how we live.

It is time for this to change. As is now becoming clear, faith in the ability of a de-regulated and privatised economy has been badly mis-placed. Over the past 30 years, inequality has risen faster than at any other time in our history, while real wages have stagnated. As it stands, we find ourselves on the brink of an economic crisis so deep that it threatens the very fabric of our society. It is time, therefore, to put ‘the market’ back in its place. We must once again conceive of it as a means and not an end. Because put simply, ‘the market’ is not enough.

By Neil Howard

But this still does not explain WHO form the ‘markets’. As I understand it, it is just an anonymous lot of men (& women?) in grey suits making judgements of their own, with no accountability, not representing anyone or even any organisation. They are not responsible to anyone & just interested in how much profit they can make regardless of the effects on any peoples or countries.

‘Markets’ were meant to be places where things were exchanged & their ‘value’ decided by what the seller was offering & what the buyer was prepared to ‘exchange’. But ‘markets’ don’t work like that anymore, especially not money ‘markets’.

We don’t have a free market. We have a market regulated in favour of big business designed to stifle competition. The weights and measures act is a classic example; it was a drop in the ocean for Tesco to change it’s equipment in order to meet the new legislation but a huge burden on small business. Corportations prop up governments in a cosy relationship that ensures they favour one another.